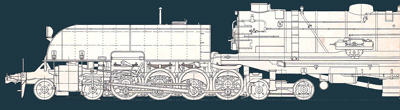

Garrattfan's Modelrailroading Pages

AD60

1.3 Chassis drive units (continued)

Instructions [62] to [95], page 11-13 of the instruction manual |

|

Next I turned my attention to completing the cylinders and valve gear. The description in the manual is rather, well let's say, "compact". If you don't know your way in Valve Gear Land you'll probably end up lost in the Rod Wilderness. So I will elaborate on this subject to make things clearer and maybe this page may help you through what most modellers consider as the most daunting part of a locomotive build.

Daunting? Yes and no. On one hand that is definitely true, period. If the valve gear does not function smoothly your loco is never going to be a fine runner. As any valve gear has nine rods and eight moving joints plus one joint for every driven axle, for the AD60 this is 12 x 4 = 48 moving joints, you have sufficient opportunities to reduce a potentially beautiful model to an annoying unmovable expensive scrap heap. How discouraging this may seem, take heart. There is also good news. The tolerances in the AD60 valve gear are best compared to the Royal Albert Hall if you have the NGG16 of Backwoods Miniatures in mind as I had. No bad word about the NGG16 of course, but here you can see the difference between the DJH mass market production model and the more sophisticated finescale builder's Backwoods Miniatures. AD60's valve gear is laid out in such a way that tolerances are spacious and the chances of interference between the various parts are minimal. The valve gears are also partly pre-assembled. This may be of advantage for the beginner builder. But if you are a beginner, why start with an AD60?? That aside, I personally hate DJH's patronizing. Why on earth do they think I cannot assemble the valve gear, while at the same time they expect me to boggle all the rest together? Now I find eight half sets of pre-assembled valve gear in the box which partly bind because they are riveted solid, riveted lopsided and also cause me great pain to debur. The rivets Eiffel tower backwards from the rods. No wonder the valve gears have such tolerances, they need to avoid stumbling over their own rivets!! That said, if some careful rework is done, it is certainly possible to make a passable valve gear from this rather crude offering.

Stop the grumbling and let's get started. |

|

|

[62-70] First thing to do is building the cylinders. All parts are white metal castings. Finding all the parts was a challenge in its own right! This photo may help you identify them.

|

|

Next you're in for a long cleaning job. Scrape, file and sand away all casting rims and burs. Drill all holes. Test fit all parts together. You'll spend the better part of an evening on it. Do not forget to sand the cylinder faces on both sides flat. |

Your fingers will have an off-day after this. The parts are tiny and there is no way to grip them with pliers as the metal is too soft for that. |

|

The whole lot being glued together with five minute epoxy. |

[68] Pay close attention to the handing of the cylinders. The four supplied cylinder castings are identical and NOT handed. However if you assemble the cylinders make sure you build two left and two right cylinders by putting the non-handed parts on the correct side of the main cylinder blocks |

|

After careful consideration I decided to follow the manual's advice to glue the cylinders, contrary to my preference for soldering.

I had two main options: -

I opted for the latter: as I am glueing anyway I'd better get the most of it by avoiding the difficulties of soldering so many small parts in such a confined space. So I glued the detail parts and soldered the cylinder assembly to the main frame. |

Note the glue gleaming from the assy. Any excess glue will come out from the joint and will settle in the edges. It must be removed. I carefully worked my way around the various joints which a fresh #11 blade. The small space between the cylinder back cover (209) and the valve crosshead guides (210) is particularly nerve wrecking to clean. Again I would have preferred soldering here as solder can be worked and removed much easier. |

|

|

|

[70] Open heart surgery: this AD60 is receiving its heart |

|

The tab on the back of the cylinder block has a sloppy fit in the corresponding slot in the frame. Make sure you push all four cylinders to the lower forward corner of the slot so they sit true and all four on the same place. |

|

|

[71-74] The valve gear motion bracket (212) and a left and a right pilot plate (213) provisionally joined. Note that the motion bracket leans a little forward (to the right of the photo. The front "legs"are just a tiny bit shorter and you will not solder it in true angles without help... |

|

... so I supported the front side with a scrap of 0.5 mm brass and soldered the three parts together.

|

|

[73] A provisional joint was made by bending the provided tabs. I am usually not very fond of this kind of help as it tends to be not accurate enough to my liking but in this case they proved to be indispensable. The whole assembly was soldered with 180C solder. |

|

[74] The motion brackets were soldered in place using 140C solder |

Say "Aaaaaaahhhh" |

|

[71] to [95] were skipped. The motion rods have to remain unpainted so they were not fitted until after the painting of the chassis. Work on the motion gear is described in 5.3 Valve Gear

|

|

|

[88] Support plates come in various sizes. Study the drawings carefully. I did the hard work for you and to make it easy, this photo. Follow me counter clockwise.

|

|

[89] After soldering the support plates (226) the long section at the rear of the pivot plate is gently folded up to match the support plate. A touch of 80C solder (preferably after tinning with 140C solder) will secure it.

|

The final result, the frames are as good as ready for painting. |

|

This concludes the construction of the drive units. Before turning to assembling the superstructure we will first do another tedious job: preparing the valve gear. |

|

Sign my

GuestBook